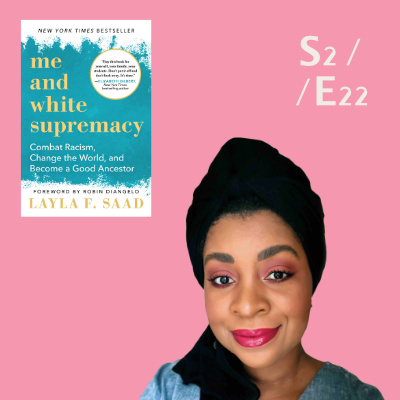

- Season 2 - Intergenerational Wisdom

- Episode 22

Becoming a Good Ancestor with Layla F. Saad

Layla Saad is a globally respected writer, speaker and podcast host on the topics of race, identity, leadership, personal transformation and social change. Aurora + Kelly talk with Layla about her NY Times Bestseller Me + White Supremacy, spiritual white women, and Layla’s work to ‘become a good ancestor’ — living and working in ways that leave a legacy of healing and liberation for those who will come after she is gone.

Released Mar 31, 2020

Hosts:

Aurora Archer

Kelly Croce Sorg

Guest:

Layla F. Saad

Production:

Rachel Ishikawa

Music:

Jordan McCree

We love your feedback at podcast@theopt-in.com

The Opt-In bookshop is at Bookshop.org

SHARE THIS EPISODE

Please leave us a review or rating on your podcast platform – it helps others to find the show.

- The Details

Transcript

Aurora: Hi! I’m Aurora. I use the pronouns she/her/hers and I am an Afro-Latina.

Kelly: I’m Kelly. I use the pronouns she/her/hers and I am white.

Aurora: And together Kelly and I are the Opt-In.

Kelly: We’re two besties having the difficult conversations we all need to be having…Because we can all OPT-IN to do better.

Kelly: Ok — so you long time listeners know, that before we record our episodes we start with a prayer.

Kelly: And some of you may be wondering why we do this…and why specifically we’re talking about our ancestors when we pray.

Aurora: Well there’s a real reason why we do this. It’s all about honoring our roots. AND recognizing our own legacies as ancestors.

Kelly: And I get it if you are skeptical…seriously! Some of us – ehem white folks – may not have ancestors we are always proud of. But for those of you who are still not on board, stay tuned cause we’re going to get into it today.

Aurora: Indeed. We’re talking to Layla Saad who is the author of the New York Times bestseller Me and White Supremacy.

Kelly: We’ve got SO MUCH to talk to her about!

Aurora: But before we jump in, just want to say that our audio is pretty different for this episode. As you notice, I am calling in by phone right now, and so will our guest. We’re sheltered in our homes like the rest of you, but we’re committed to bringing episodes to your feed…Okay, let’s jump in!

Kelly: Hi, so our special guest here with us. would you be able to share who you are and your pronouns with us?

Layla: Hi everybody my name is Layla Saad. And I use the pronouns she her hers. Well it feels like we’ve known you forever. But can you share with us about where you’re from and some key highlights of your journey thus far.

Layla: Sure. The thing that a lot of people probably know me for is my now New York Times best selling book, Me and White Supremacy. Me and White Supremacy began as a Instagram hashtag challenge in the summer of 2018. I led many, many white people through a 28 day process of examining, understanding, unpacking their white privilege and their unconscious racist thoughts and beliefs and behaviors. The challenge went viral, which then a few months later turned into a workbook that I self published that also went very viral and is now available as a hardcover book and audio book and an e-book. And I began this work in the summer of 2017 following the Unite the Right rally that happened in Charlottesville, Virginia, where we saw modern day Nazis locking in the streets with torches and screaming racial slurs. And it really shifted something very deep within me. In terms of my personal identity, as you can probably tell my accent is a little bit mixed. And it’s often hard for people to place me when I’m in the US. You know, like you sound really British. And then when I’m in the U.K., the like, where in America are you from? And so it’s always confusing to people. So for context, I’m a black Muslim woman. I’m East african. My mother is from Senegal. My father’s from Kenya. They have roots in Oman, which is here in the Middle East where I live. But I live in Qatar. I was born and grew up in Wales and then I lived in Tanzania and then in Wales again, and then in England and then in Qatar. So I’m very much an international, intersectional person. I’m a third culture kids, meaning I grew up in a culture that was not the culture of my parents, and white supremacy really shaped a lot of who I am and how I saw myself. And so much of my work is driven by my own desire and need for my own healing and for the healing of black people and people of color around the world.

Aurora: Beautiful. Thank you for sharing that love. So I’d like to understand a little bit more when you talk about healing, right. So there was an incident that prompted you to sort of dig deeper, to sort of ask spiritual white women. And I also want to ask that question, why spiritual white women? But the second question is the healing part, because the healing is connected to an impact that you have experienced from white people.

Layla: Yes. So why spiritual white women? And it really took the forefront actually around my 20s when I struggled with lots of anxiety and depression.I look back now and I’m like, oh, my poor, like 20 year old self was struggling to understand her identity and who she was and who she saw herself as within white supremacy. Back then, I was just a hot mess, basically all into the world of personal growth and personal development and these books and these classes and these teachers really helped me incredibly. When I look back now, I see all those teachers and authors were white. Their whiteness, didn’t take away from what they offer to the world. But it also didn’t speak to me specifically as a black Muslim woman and didn’t speak to how a lot of the things that we are collectively healing from in the world are because of whiteness. I had just learned how to survive within whiteness and I hadn’t really learned how to question why are all these teachers white and how does their whiteness impact me in ways that I am unaware of. But what I began to really have deep internal reflections around was how has being a black woman in the world within whiteness shaped how I see myself? What did I internalize being born in to being born as a black Muslim girl in predominantly white Christian spaces? What stories did I tell myself about what that meant and what stories did society reinforce to me about my identities and then how did that form who I think I am? Who is this true self that I think I am? In what ways is who I am defined by who I say I am versus what white supremacy says I am? I remember watching this interview with Toni Morrison and she was talking about white gaze. And I was like, what is the white gaze? I’ve never heard this term before. I go down the Internet, you know, rabbit hole and find out about the white gaze is how the world is seen through a lens of whiteness and how we see ourselves through whiteness. And the question that I just stopped me in my tracks was: do I know who I am outside of the white gaze? And when I really start to think about it, I realized I didn’t know. I remember at the time, I was just like, I’m taking a month long sabbatical, like I need to step away from everything because I just realized I don’t actually know who I am outside of what whiteness says I am. Because as much as I’m saying white people don’t treat me this way, I don’t know how to live any other way. Right. And so a lot of the work that I’m asking people to do, white people is OK, you need to do your work on white supremacy, but I also have to do my work. Because let’s say we get to a world in which all white people are doing the work of dismantling white supremacy. White supremacy gets dismantled. Who am I without whiteness? Do I know who I am? Do I know how to exist? If it were to disappear today and I haven’t defined for myself who I am, what will happen to me? I’m asking white people to heal themselves. I need to heal myself.

Aurora: My goodness. Everything you just said hit such a chord. And is why when I think we speak, we as people of color speak that our liberations are intrinsically linked. That is to what we’re speaking to, which is not just that white people, white folk have to do their work, but that be equally as people of color have to do our work and the healing of our traumas and the real unpacking, the disembodying and then recollecting of who we are at our core, at our truth and at our essence.

Layla: What is really the mind fuck of all of this is that we have to heal ourselves as as people of color while still existing within white supremacy systems. Right. So society continues to reinforce the messages of our inferiority but we have to create our own personal universe. Right. So we live it. We absolutely live in the collective universe where white supremacy exists. We don’t deny its existence. We don’t deny racism. But we have to learn to also cultivate our own personal universe and understand that our personal universe is the actual truth. My personal universe says I’m not superior or inferior to anybody on this planet. I do this very, very hard work, but I don’t do it from this place of brokenness, woundedness, resentment. I don’t do it from this place of: I can’t be healed until white people see me as a whole person. I’m already a whole personIn the beginning a lot of the frustration with white people, especially women of color to white women, is why don’t they just get it? Why is it so hard that it’s conversation? And I remember feeling really burnt out in those early months. I was just like, this isn’t sustainable. I am everyday having conversations that are quite challenging, heated, frustrating online with white women who are just not getting it. And I don’t understand why they’re not getting it. And the real crux of it was I was waiting for them to see me before I could see myself. So I had to completely flip it. I had to learn how to see myself. And not care about whether you saw me or not.

Aurora: Yes. Yeah.

Kelly: And I would also offer that I know that I wasn’t fully seeing myself. Without my whiteness, who am I? I know that was not there. And doing your Me and White Supremacy Challenge over a year ago when it was in the workbook stage was definitely one of the most excavating opportunities I’ve ever had. That’s why I can’t say enough about your book and what you do because it came through you. And it hits on things that. I didn’t know they were there. I didn’t know they were me. I didn’t know. I didn’t know who I was without them. Yeah. And then I could actually be free of of a lot of those cultural characteristics in finding out who I actually was.

Layla: I remember during the Instagram challenge, one of the things that I would bring people back to again and again is this question of you have to redefine what being good means because so many people are trying to show up in this work while still maintaining or trying to cling on to this idea of being a good white person, that I will engage with this work but really, I’m actually one of the good ones. I read the books, I listen to a podcast. I’ve gone to the classes. I know all the words in the name. So I’ll engage with it. But I’m actually one of the good ones.While behind the scenes, there’s so much going on unconsciously in terms of racist thoughts and beliefs and actions and things that you think nobody will see you doing or things that you think don’t matter that much. And what I’m asking people to do is to tear down that mask and really look at what is going on behind the scenes. And can you now consciously, intentionally rebuild yourself and redefine good as not being perfect or never does anything that can be perceived by others as being racist, but rather being in a constant state of practicing anti-racism. And there is a huge difference between saying I’m not a racist vs. I do my best every day to show up in my anti-racism practice.

Kelly: So why do you think right now, Layla, that it’s so critical for white women who hold white privilege to do this work and to ponder this work, especially at this moment in time?

Layla: I think the sense of urgency that’s coming up now isn’t one that is coming from people of color, but it’s coming from a realization and awakening from white people and white women, especially in the United States where the election of the current resident of the White House caused many white women to to wake up. It’s now coming to a point where it cannot be avoided. And there are things that people could have gotten away with before that now you just cannot get away with. And I think for many of us, people of color, we have just reached a point of enough’s enough. We’re just we’re rising up in a way that we’ve always done. But we weren’t as connected in the same way because we didn’t have social media.

Aurora: Absolutely. And so as you see sort of this rising of engagement, rising of awareness across white women, where do you also see them get stuck, Layla?

Layla: One of the things that just rubs me the wrong way is when white people complain about other white people. And it’s this sort of separating of, aren’t white people the worst?! And unlike these include yourself in that.

Kelly: I used to do that.

Layla: Yeah. Aurora is like nodding your head emphatically.

Kelly: Yep.

Layla: And one of the other ones that happens and I think a lot. You know, I’m talking to a deal that is, you know, a woman of color and a white woman. Right. So the sisterhood, the friendship. So another tipping point for many white women is feminism and white feminism and a misunderstanding that mainstream feminism was never meant to serve women of color.

Feminism, as we understand it, mainstream feminism is only about the struggle under gender. And so when it’s only about the struggle under gender, black women and women of color are asked to chop parts of ourselves in order to fit in to a feminism that doesn’t really serve us. And so even if we get to OK, so we smash the patriarchy. OK. We take it down. We have gender equality now. We still have racial equality. So women and men are not equal, but white women are now equal with white men.

Aurora: And and that’s so interesting because Kelly and I talk about this a lot. You know, I spent most of my life in corporate America.

To a degree there’s a part of me that felt more marginalized and more hurt by the actions of white women because of their level of unconsciousness and unaccountability.

Layla: Yeah, I think. I hear you saying. I also think part of the reason why it feels like it hurts more from white women is because we collectively internalize a message about white women’s perceived innocence.

Aurora: Say more about that.

Layla: Yeah. When a white man says something that seems like, oh, very feminist or very woke, he gets rounds of applause. Right. Because he’s like – the bar is so low. But with but with white women, there’s this other perception of white women can do no wrong. The purest sense of what a woman is. And so if you think about what we as women of color don’t necessarily consciously believe, but are unconsciously fed this message all the time, which is the way to be a whole woman, is to be a white woman. The lighter skinned you are, the more of a woman, you are. The straighter your hair, the more of a woman you are. The less shapely you are, the more of a woman you are. And so on and so forth. Right. And so there’s this wound I think for us as women of color of this is the woman that I’m being told that I have to be like and she’s harming me.

Aurora: I talk about this where I spent twenty six years straightening my hair day to go to work

Layla: Right. And the irony of that is. Which is what my mentor always reminds me of is a very strict horded life. Is is it is an Africa. Right. So we are we are this, we are the source, we are the blueprint, we are the beginnings, we are where womanhood comes from. Right. And obviously, you know, race, it is a social is a social construct, not a biological fact. But the first woman was a black woman. We are not. We are not. We are not for deviation. We are the beginning.

Kelly: Yeah. Layla, I have a confession for you. The first time I ever thought of being an ancestor, let alone being a good one, was in your mention of being a good ancestor. And I just know Aurora has always called in to and prayed too, and given thanks for her ancestors and that and it’s very new to me. So I was just wondering if you could share some thoughts on how people who may not think in terms of being an ancestor can both either break that pathology. And maybe in that they’re grappling with, you know, some ancestors who may not have been good ones because I thin that’s what keeps me from it as well.

Layla: I host a sister podcast and this is a question that I know that many of my white guests struggle with. Right. When I ask them, what is it? Who are some of the ancestors who influenced you in your journey? What does it mean to be a sister to you? You know, the really struggled with these questions as as black people and people of color our ancestors are a source from which we draw great pride lessons, resilience, creativity. Like without that action it is hard to know how to survive, let alone thrive within white supremacy. One of the tradeoffs, I think, for people who are white is to cut themselves off from all of that and to really just see themselves as individuals.

You can honor your ancestors. There are grandparents, great grandparents, great aunts, great uncles, people who, you know, in history who you have learned a lot from, whether from their mistakes or from their successes. Honor them, honor those people because you came from them. At the same time, the call to white people in this time – for me the call that I am making is you have an opportunity right now to leave a different legacy behind than the legacy that was left to you. But there are people that will come after you are gone who will either because of your actions, continue with this legacy of whiteness and harm to people of color, or you do the courageous hard work now in your lifetime to set an entirely different trajectory so that people who come after you are gone are showing up in an anti-racism practice, taking accountability for the harm that they pose in their answers, since employers are doing everything to make sure that people of color are uplifted, elevated, supported. That is something that you set in how you show up in your lifetime.

Kelly: Yes. Gosh, Leila, you know, it’s it it. You you always get me thinking along the lines of ancestry. And it really does. Become where it’s a part of my day to day deconstruction and realization, constant realization that everything I say and everything I do has been grown in a white supremacy petri dish.

Kelly: So thank you. Thank you for your work and your and you’re helping me become aware of being an open and vulnerable and accountable ancestor.

Layla: Yeah. And you know, it’s not to say that your ancestors were bad ancestors.

Kelly: Totally. Totally.

Layla: How they lived informs how you live, what you see and what you believe about yourself and the world comes from what they saw and believed about the world. And so we often talk about ancestors and we think of them as like these five like old wise beings who’ve sort of ascended and, you know, didn’t live any kind of life where they struggled or they had to call on their courage or they had to really question everything. No. Like we’re living it now that we are living ancestors. We could be – God willing, you could drop dead tomorrow. And you have to really question, did I really live the way that I wanted to live it? Am I leaving behind a legacy that leads to the kind of world that I know that we should be living in, that I hope that we would be living in. It’s always the time of the current generation to be thinking about what will I leave for descendants after I’m gone?

Aurora: So Layla, you know, you you over the last several years, you’ve produced and released an incredible gift to all of us in White Man, White Supremacy, the handbook, the book, your tour, your podcast. What is the world you envision? What is the impact that you are hoping your work and your presence here on Earth has?

Layla: Yeah. What I want to create as a good ancestor, I really want to create what was left behind for me from good ancestors, people who I am related to and people who are I’m not related to, you know, leaving behind the memory of how they showed up in the world and the archives, the artifacts of what they left behind.

My children are going to be facing a world that is a lot worse than what we are dealing with right now. We need to equip them. We need to remind them that it that they are not alone, that their ancestors also experienced challenges. This is how they survive. This is how they thrive. This is what they offered. This is how they taught. This is how they changed people’s minds. This is how they offer transformation. And however, that shows up for me in some regards. It’s a podcast. It’s the writings. It’s I would love to have a documentary. I would love to do so many things that I want to leave behind.

Aurora: Indeed. Absolutely beautiful, Layla. And it reminds me of of the things that it reminds me of the work that Kelly and I are doing. And how do we leave behind or a model of intersectional friendship, that is heart center, accountable, raw, but focused on the betterment and healing of our selves of each other. And hopefully is an inspiration as a model is an example for the collective.

Layla: Yeah. I really need blueprints and models. We are not only in the work of dismantling, we are also in the work of rebuilding after the dismantling, then what? Right. So we look at your friendship, a white woman and a woman of color and without any understanding or real deep conversation around white supremacy and racism, tou know, there’s often this feeling of, well, we’re friends, so we should just love each other and that’s it. Racism has nothing to do with our friendship of love with each other. Right. And so you introduce, now we need to have a conversation about race. And it sends some white women either into, you know, or into because I love you. I will show up for this work. And I talk about in the book that one of my best friends was a white woman. And when I started talking about racism, she entirely retreated herself from our friendship. And when I asked her, why have you not shown up for me? You see that I’m talking about racism every day with white women. I’m being attacked. I’m having all of these experiences. You’re my friend. Why are you not showing up for me? Her response was well other – notice that other women of color and black women were showing up for you. So that abdicated you of your responsibility and our friendship. Right. So the sisterhood was there for as long as I didn’t talk about race.

And so when I look at you, a black woman and a white woman who are, you know, our friends that also do this work together. And that and that, you have to find that harmony between having very real and honest conversations. Kelly being accountable, Kelly, you having to really watch how you take up space in in the friendship and in the conversation. Aurora, with you feeling safe enoug in the friendship to really, you know, fear, fearful and true self. Like that is long term work. And so that requires and requires really long term work. And when the dismantling is done and when we have the world that we say we want to live in, we’re not going to live in our silos. We’re saying we all got to live free and together we’re not going to live in our silos. And so some of us are doing that, rebuilding work and modeling as you, too, are.

Aurora: You know, I’ve been at this for a while for a while. And it was a blessing and a curse that I traversed most of my outside of my personal life in corporate America that I hit up again so much. And never fitting in and always being the outlier and always being the angry black woman, the disruptor, the true slayer. Like all of that. Right. Like all of that really drove me back to myself that I think allowed me the opportunity to show up in a friendship with Kelly from a place that says, you may not be recognizing what you’re doing. I’m going to share with you a perspective and you get to decide whether or not going there is what you want to do for yourself in this moment in time. But for me and what I need out of my friendships. It’s going to require a greater sense of awareness and accountability.

Layla: What it says to me is that you have absolutely been in this work for a long time, your own healing work, that you clearly know what your boundaries are for yourself, what your standards and needs are for yourself, and that you are very comfortable expressing that, asking for that.

And so that honoring of yourself in so key. And I think for a long time for me, because I’d grown up being the only black girl. There’s this picture of me when I was in Wales and a kid gone to a friend’s birthday party. So it’s a row of girls standing – all white. And I’m the only black girl in the picture. And all the girls are in white dresses for some reason. I’m not sure why this was the case. I was in a white dress that had every color under the sun on this dress. And I had these beautiful like multicolored ribbons in my hair. And I just stand out as the only black girl wearing the brightest dress and for so long. I remember feeling shame.

So there’s a lot of healing work that has to be done.I will never sacrifice what I need for what you tell me I should accept.

Aurora: Oh, my God, that is it. What I need versus what you deem I should accept.

Layla: And in a world where -we’re talking about how a black woman is seen – as black women, we are taught that we should accept this much right, the as small as possible.

Aurora: And we’re lucky that we even got that much.

Layla: Right.

Aurora: I cannot tell you how many times I was told in my career. Oh, you were so lucky. And I’m thinking lucky? I’ve worked my ass off.

Layla: Right. Right. So when we bring that into the dynamic of friendships and sisterhood and women of color are saying, this is what I need -this is what, you know, is often quite challenging for white women to understand what’s going on and to accept it.

In order for me to feel seen by you, in order for me to be able to show up as my true self to be vulnerable and trust you. And trust that you understand what your whiteness introduces into our dynamic that you need to be engaged in personal anti-racism work. Without it I am willingly, knowingly putting myself in a very dangerous situation.

Aurora: Yes.

Layla: And and we go back to, you know, I use the word “dangerous” and I know white women hear that they get prickly in their clutch, their pearls, because it’s like, I’m not dangerous. I’m a nice woman. And again, it goes back to that perceived innocence of white women. I’m not saying white women are villains, but I am saying you’re conditioned into white supremacy, your sense of feminism centers you at the expense of everyone else. You don’t even know how you’re causing harm.

Kelly: Yeah. Thousand percent. You know, Anthony DeMello, what does he say? That people don’t want to wake up. And I feel like that often times in in this journey, I’ve just learned that it’s just the quickest magnifying glass to how I handle all of my trauma in every aspect of my life. And then if I really want to wake up, the quickest way to wake up is through this work. And it’s a gift in that.

Layla: Yeah, and the reason so the reason I love that is because white supremacy conditioned you in the same way that it conditioned me as a black woman to believe certain things about myself and then how I shop in the world comes from that route – it conditioned you in the same way. And that applies because it’s not just about in the realm of anti-racism work. It’s how you see yourself as a person.

So let’s talk about, for example, perfectionism. Right. We talk about, oh, I’m a perfectionist or I’m a recovering perfectionist. As a black woman, where my perfectionism comes from is trying to survive within white supremacy. My mom said, you’re black, you’re you’re Muslim, you’re a girl. You know, I was so young. And she said these things, these three things will work against you and you’re going to have to work harder so that they don’t work against you. And so my perfectionism comes from I’m making up for the fact that I’m not a white man. Perfectionism for white women comes from – I think part of it is understanding the gap between white men and white women. So definitely like patriarchy, sexism. But also have you noticed how you are safe as a well woman within white supremacy as long as you do not go poking the beast of white supremacy. As long as you don’t start doing any anti-racism work or having very direct conversations with other white people about white supremacy, you’re safe. But the minute you do do, the whole thing gets switched on you. And suddenly you’re painted as something else. Right. We as black women know what this is like every day. This is this is our reality of living within whiteness. We were never afforded this image of being the nice black girl. Right.

But with white women, it’s you can have the privilege of being a white woman as long as you are innocent, kind, nice.That sense of perfectionism is a way that all of us are trying to survive within white supremacy, but from different angles.

Aurora: Yes. The healing is the coin. We’re just on opposite ends of the coin and the coin is connected to our Mutual Liberation. Layla, we have one parting question for you, which is what would you like our listeners, our audience to opt in to?

Layla: Yeah, it’s always do the work to to show up as a good ancestor. Show up for black women. Those are those are the two things that are always, that are always there.

Aurora: And give us an example, because I get this question. What does it mean for white women to show up for black women?

Layla: It’s understanding that, as we’ve been saying again and again, white supremacy has conditioned you to understand certain things about yourself and to understand certain things about people of other races and genders. And the undoing of that understanding has to start within. So a huge part of it is actually doing work behind the scenes where nobody sees you, where you’re with yourself, doing that self awareness work, doing that self reflection work, really unpacking, really examining.

So the first place that you start is actually with yourself, then listening to black women and women of color. And so make it your responsibility to curate your own learning around this so that the you’re not just listening the black women who make you feel the most comfortable. And then, you know, in your friendships, at work, in your families, showing up, asking what is needed, looking at the way that you take up space around black women. Not assuming that it goes saying that black women need rescuing or that we need saving.

When it comes to speaking with other white people, speak up. When it comes to being around black women and women of color, shut up and listen.

Kelly: So lastly, what is next for you, Layla?

Layla: So even though we are in a global pandemic, you know, we have to stay with our vision and the things that are. I was journaling this morning and I said, I am not the waves, I’m the ocean. The waves is what’s happening up top. Right. So there’s a storm going on up top. There’s like huge waves, like it’s just it’s dark, it’s stormy. We don’t know what’s going on. We don’t know when it’s gonna be over. But underneath at the bottom is the same. At the bottom of the seabed, it’s consistent. It’s the same, nothing changes. Right. And so I had to remind myself, you’re not the waves or the ocean. You set yourself some goals. You have a vision.

Your job is to keep walking through it, especially during these times when people are really needing leaders. Messages of integrity. So this isn’t an excuse or a time for me to pull back. It’s actually a time for me to step forward. I’m stepping forward and continuing on with my my vision. And that is to to build this long lasting good ancestor academy that will host these classes and these e-books and other things, you know, that will help to educate people and inspire people and activate people. The next book is the young greaters edition of Me in White Supremacy. And so. Yes. Yes.

Kelly: I can’t wait to get those 20 copies.

Layla: We’re writing this book and it’s for kids aged 10 to 14 aimed at kids who have white privilege, taking them through a 28 day process and really empowering them to understand things in a way that the adults in their life haven’t had the benefit to understand about what racism and white supremacy. We have a type of charity in Islam that’s called ___ and it’s a charity or a good work in the world that outlasts your lifetime.

Aurora: Beautiful.

Layla: Right. So I think about my books and my classes and my courses and whatever archives I left over so that people can can reference and look back to.As hard as this is, nothing in my life has ever felt more true, aligned where I’m supposed to be in-flow than doing this work.I am exactly the right person to do what I do.

Aurora: And thank God for that. Right. We all thank you and praise you and have an enormous sense of gratitude for your work.

Kelly: We could talk to you the whole quarantine.

Kelly: Now everyone go buy Layla’s book because we ALL have a lot of time on our hands, so let’s make the best of it. And, YES, Me and White Supremacy, is available on Kindle.

Aurora: Thank you all for tuning in. Keep your comments coming in, keep the love coming in. Find us on the socials @theoptin.

Kelly: Music for this episode is by Jordan McCree. And the Opt-In is produced by Rachel Ishikawa.

Kelly: Bye.