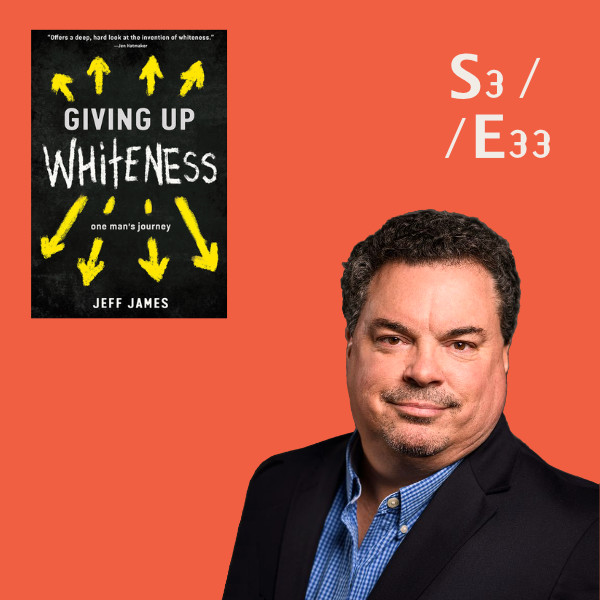

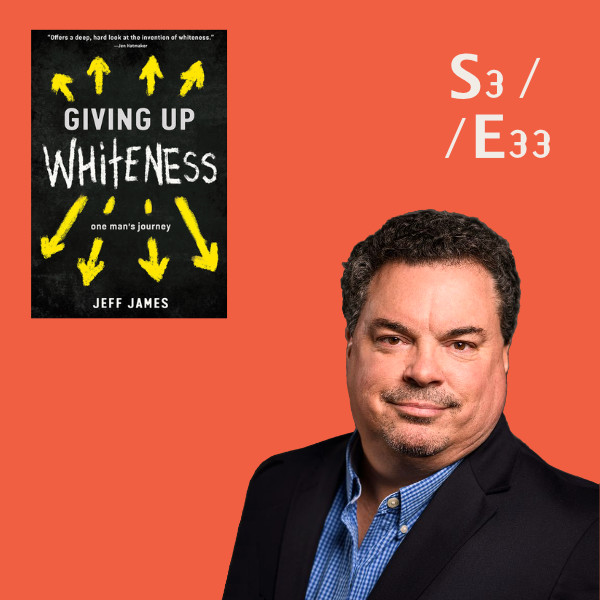

- Season 3 - COMMUNITY

- Episode 33

Giving Up Whiteness, Gaining Humanity

Jeff James was one of the good white guys—or so he thought. But when he asked an African American friend how he could help fight the rising tide of racism, he had to think again. “Simple,” she shot back, “get rid of whiteness.” Thus began his journey to discover, name, and dismantle the racial category that had defined and advantaged him for a lifetime. Aurora + Kelly sit with Jeff as he shares his discoveries on just how deeply the forces of race have shaped his own choices and how the things we can’t see yield the most power. Us well-meaning white people have a lot of work to do and it’s past time to Opt-In.

Released Nov 10, 2020

Hosts:

Aurora Archer

Kelly Croce Sorg

Guest:

Jeff James

Production:

Rachel Ishikawa

Music:

Jordan McCree

We love your feedback at podcast@theopt-in.com

The Opt-In bookshop is at Bookshop.org

SHARE THIS EPISODE

Please leave us a review or rating on your podcast platform – it helps others to find the show.

- The Details

Transcript

Aurora: Hi — I’m Aurora.

Kelly: I’m Kelly.

Aurora: And you’re listening to the Opt-In.

Kelly: So I don’t know about you all, but I am recovering from a very long two weeks. With the election and COVID…it’s been a lot.

Aurora: And maybe you’re like us and ELATED that President Trump is voted OUT… But here’s the thing…our work isn’t over.

Kelly: No it is not. And for white folks, we still have a lot of unpacking to do. We need to abolish with white supremacy. Which means, we need to address the white supremacy characteristics within ourselves.

Aurora: So here today, we’re talking to someone who’s been doing that work.

Kelly: Our guest today is Jeff James, who wrote Giving Up Whiteness. This book tracks Jeff’s journey of dismantling whiteness within himself.

Aurora: We got a LOT to talk about so let’s get into it!

Kelly: Welcome, welcome. Thanks for being here today. Would you mind introducing yourself and giving us your pronouns and maybe sharing some key things about your journey thus far?

Jeff: Thank you. And I’m Jeff James, the author of a new book called Giving Up Whiteness, also a book publisher myself. So that’s kind of been interesting in its own right pronouns, he and him, and really just been very excited. I’ve been on a on quite a journey in my life on the topic of understanding, equality, understanding, inclusion and understanding identity. And in our culture sometimes very much so that’s wrapped up in race. Growing up on a very small Appalachian town in central West Virginia and very, very, very white part of the country, maybe the whitest demographically. But my journey in some interesting ways sort of intersected me with a lot of diverse people, mostly because of my my father was a college professor. And so the college campus environment started introducing me to people that if you normally grew up in central West Virginia, you don’t get exposed to. So so that’s a big part of, I think, some of the seeds that got planted in my life about why I was even open and interested and curious about these ideas.

Aurora: So, walk us back to – you shared that the seeds of the curiosity left how you articulated the seeds of your curiosity and openness to nonwhite people likely began as you visited your father on college campuses. He was a professor, but you also had a pretty long corporate career. And so I’d love for you to to talk us a little bit about that journey. And what were you noticing?

Jeff: The first thing I mention, the reason you mentioned what has just happened in Philadelphia, literally five years ago, I moved to Nashville and the same wave of violence against in the case five years ago, unarmed African-American people by law enforcement primarily. But it was particularly the shooting, this horrible incident in Charleston, South Carolina, at the church where people were murdered that sort of put me over the edge and that sort of started this more intense journey because I had always considered myself one of the good guys. I’m on the right side of this here. I’m trying to work for equality. I care about diversity in the workplace. I was often one going down to H.R. saying maybe we should do some diversity initiative, all that sort of thing. But it was really the intensity of that summer. And I tell sort of sort of an opening part of the book where I texted my friend Crystal, and she certainly is one of my guides who’s sort of a costar in the book, if you will. But I literally just said, Crystal, I mean, this is insane. Like, we’re just we just keep going backwards. What is going on here? How can I help white people become anti-racist? And, you know, it’s funny because at that time, I’m not even sure that I could be defined. Now, in my understanding now that I was anti-racist then I was what? Dr. Kennedy, Ibram Kennedy, if you, of course, know him, he would say there’s segregationist, there’s assimilationist and there’s anti-racism. And I think many, many people that were in my sort of state of mind throughout most of my life that do want to see good happen or in that assimilationists category. And I probably was then when I texted that message to Crystal and her response was the sort of disorienting response that caused me to go on. This much deeper journey, she said, is very simple. White people are not white, get rid of whiteness. And I was like, OK, I didn’t know that was possible. I didn’t know that’s something that was even. Is it immutable or not, you know, this whole concept of race. And so that really sparked me on my journey to even understand what in the world is race, what is whiteness. What is the under. What are the underlying. Cultural assumptions that we’re all operating off of that keep leading us down the wrong path. We keep trying. It’s that whole definition of insanity thing. We keep trying. We keep failing miserably. And it’s like this crazy pendulum of back and forth and whatever political winds are flowing. But that that’s really what got me on this path is, wow, I couldn’t even tell you what whiteness was. I really at that time, I didn’t even understand. I just thought it was like, OK, I have brown hair, I have brown eyes. I’m from, you know, ancestry from Europe on this map. So therefore I must be white. But I didn’t know what white was.

Aurora: Well shout out to Crystal.

Jeff: Yes, yes, very much so.

Aurora: And for those who may not have read the book yet. So Crystal is your…?

Jeff: She’s an amazing friend. I met her when I moved back to my home state of West Virginia to start a consulting firm and do some economic development activity in the state and tell the story of how we actually match. It was during a time in Charleston, West Virginia, when a major sort of racial incident had occurred and we were called together by the local Chamber of Commerce, of all places, a very visionary woman there who wanted who knew that I was working on some of these economic issues. And she was smart enough to attach economics and diversity to together. And Crystal was just this amazing artist, poet, activist. There’s so many things that she does. It’s hard to really describe her with justice. And she’s a black woman. She’s she is in the in the language of our culture. She would be considered biracial. Her father was African-American. Her mother was white. So.

Aurora: And not that we’re putting the burden on Black and biracial and Brown people. But, you know, I just think there’s something to this this sparking. Right. And this speaking of speaking to truth in moments that I believe create vibrational catalyst and because that’s what it looks like happened for you, Jeff, there was a response that Crystal shared in that message back to you. That just sort of made you pause and say, what is white, what is race, and so what did you find?

Jeff: If she if she had texted that back without the history that we had together, it probably would have bounced, it would have been frustrating, but because we had several years together slugging it out, trying to understand each other, and she ended up working at my consulting firm. And I tell some stories that sort of lead up to why Crystal is such a great friend through those experiences. But I saw in her not only the passion for justice and passion for equality, but I saw how tired and frustrated that she would often get during these various experiences that we do have together. And without that learning and trust me, there are times that I thought she hated me. She was, you know, like she’s not a big fan of me. But in reality, she was reacting to years of, you know, having to be the one to explain things all the time. And she certainly played that role in Charleston, West Virginia. I mean, she was the one who many all white boards of directors or all white leaders would say, well, let’s get some feedback from the black community and let’s call Crystal, because she was being that one, willing to do it. So just with that history in mind, the trigger of of that interaction, because I still was very disoriented by her response. It felt a little it felt like she was maybe angry. She texted it. And I sort of interpreted that for a second. But then I just really I don’t know what it was, honestly. It was sort of a spiritual thing that I. Accepted it, I let it sort of seep into me, and that’s what allowed me to start questioning, start the questions that I needed to start asking myself because I had never been asked that before. So. It’s it it is a spiritual thing, it’s a very difficult thing to write a book for anyone. It’s a difficult thing to do it when you’re busy and you have to do it on weekends. And I’m sitting at Starbucks and, you know, every weekend just pouring out thoughts, pouring out things that were coming to me, but also just writing down all the questions like how is race? How’s whiteness affecting me right now, just as who I am. And so you see that in some of the chapters. You know, how how does it affect who I dated in my life? How does it affect how I chose where to live, even even now? How how does it affect where I work, who I hire, where I worship? I mean, it’s just a million things and you just start having this series of aha moments that so much of life is shaped by forces that we don’t we’re not even aware. And I almost sort of compare it to oxygen. Right. You’re born and you have oxygen. You don’t really think about it. Yes. In this culture for quite some time, I think it’s starting to change because our country is becoming far more diverse. But when you’re considered white, when you’re labeled white, you just sort of grow up in oxygen. You don’t even notice it until you start having interactions that disrupt the the assumption. And again, I think that when I was a small child, there were seeds planted that made me even care about other people in a way that would open me up to this. But certainly as I went forward in my career and had more friendships, moved to Philadelphia and had a lot of diverse friendships, you really only have two directions. You can either become incredibly defensive and start disengaging or you can become curious and empathetic and want to know what is going on here.

Kelly: I love seeing the journey of transformation in your book, because you really start with such an amazing, concise history, history in which I haven’t I’ve never read a lot of the all the history books I’ve read about race, the way you you really packaged it up. I was like, oh, and then you move into kind of claiming and and taking accountability for your racial identity and kind of then reflecting that into parts of your life to see like how about this? How about that? How about this? And then you’re showing that you have the stamina that you just keep on teasing, you know, you’re not done right. And it is never over. And you bring a level of joy to it and and wholeness and humanity and an ownership. So I want to start back to the to the history part. And what you encapsulate it here: it’s an entirely different thing to unite multiple tribes around a superficial commonality such as skin tone, provide a religious justification for your endeavors and embark on an economic fueled injustice on a global scale that will lead to more than 60 million human deaths and the ruination of the lives of millions more for generations to come. The weight, yeah, of that, that we disregard and deny and justify. To me in reading what you wrote, it was undeniable once you understand that once you know that you can’t unknow it, and so if you could just tell me a little bit how did that feel or what moment did you know that this was this was something that this was changing your life, that this was going to be forever?

Jeff: Yeah. Yeah. Well, that’s that’s a great question. The challenge is that race and in the category that I was assigned, whiteness, it’s an abstraction. It becomes like this. Like I said, it’s sort of like you don’t notice it, but it’s a it’s an abstraction. And the reason why I think a lot of people labeled white are defensive is because when you start calling attention to the abstraction, it’s incredibly uncomfortable. And a lot of people have written about this white fragility and a lot of other sort of good books, but. The the questioning of the ground underneath you is always disorienting, and that’s why Krystal’s text, even for me, I was sort of primed to be interested in this sort of thing, but her text was still disorienting towards me, you know, when I when I felt that. So you can only imagine, you know, obviously people that are less aware of the abstraction, less aware of the sort of made up nature of all this stuff, how disorienting and confusing and emotionally jolting this really is. But to get to your question about history and learning about it, how how that felt, you know, I was the guy in college who read Autobiography of Malcolm X. Not a lot of my white friends were reading that book. So just to sort of let you know that even with me there throughout the next 20 or 30 years, I still didn’t quite understand the depth of what you just read. I mean, that’s that’s sort of what you just read was sort of the fruit of realization of, wow, wow, you know, slavery that’s so bad. You know what? I don’t know why we would allow that or the history of such and such. But until you really look at it and really look at the the scale the scale of racism just blew my mind. I think that was the biggest. Aha moment is. Yes, people have always been divisive. Yes. There’s always been war. Yes, there’s always been slavery. Yes, there’s always been murder. There’s just a horrible history of humanity sometimes. But what did race bring to the table? It was an envelope again, this abstraction of evil that started to layer over the justification of a wave of human history, mostly European colonialism, that. There was a reason why it was applied, it was there was a reason why whiteness was invented, there was a reason why race as a, you know, basically faux category of science was invented. And there’s a reason why it took hold because it served a purpose. It had a true economic purpose. And when you start realizing that and then you said, well, how did they get away with that? I mean, it’s you know, if I wanted to go start a business, I couldn’t just go enslave people. So how did this happen? Well, it happened because there was then a lot of collaboration between the Christian church, you know, as it existed in medieval and later into later European history. I mean, there’s a reason why the theology of Christianity was perverted in order to justify enslaving people, robbing them from a continent, going into the North America, South America and doing what what was done. There had to be an underlying philosophy that allowed human beings to do that to other human beings. That’s what happens. And so there is a need there is a theology or a purpose behind it. And then the scientific part, believe it or not, was really kind of the third part. It wasn’t even the main part. You know, we had some scientists of the day who started looking for differences that they could then connect to the reason why it’s OK for us to subjugate people. I mean, it’s a it’s a really amazing cycle. And then to see the level of destruction throughout history that that that led to. Yeah, that was that was a weekend of. You know, feeling a little punched in the gut when you realize just how evil works and on what scale evil can work, and that’s why it’s so scary and it’s so important that things that we’re seeing now in this country are things that we saw in Germany leading up to it. People kind of feel like you’re exaggerating a little bit when you start ringing the bell, the warning bell. But these are the same things. These are the same abstractions and theories that lead to what we have seen.

Aurora: because it’s the same oxygen, Jeff. And so I want to ask two questions, because, Kelly, you said, you know, you you were huge historian, a huge biography reader. But you still didn’t get it because that’s actually how I feel. I feel that the history is there. If you if you want to Google the history and know what the real history, it’s there. And one, I think in part, we’re not proactively taught it. So you have to actually be curious enough to go find out about it. And even if I find that even when people, white people find out about it, I’m not sure that they’re connecting it, that they’re kazal connecting what? Connecting it, period, and understanding the magnitude of the harm, evil and damage that sits at the root of our beginning. And so I appreciate you saying that maybe you may have known some of those pieces, but the part that seems to have connected with you is the scale, because somehow the connecting of the data at the level of scale was not as visible to you, despite having maybe known some of this history or known some of this knowledge.

Jeff: Well, I think it’s scale, but I also think the other element that is. More difficult to get is the interconnectivity of how it all worked. You know, I’m saying so. And, you know, I grew up in the church. I grew up as a Christian. I grew up. You know, you really just are very bummed when you learn church history. Yeah. And in some of these things. And so it’s you know, that may have been one of the biggest things that emotionally I had to get over is to recognize and acknowledge the role that my the practice in a at least in certain formal ways, was responsible for a lot of what we’re what we’re talking about. If you don’t have that understanding of connectivity, of how the theology helped justify the economic and the scientific and all the different, it’s easy to compartmentalize and just feel like, wow, that’s really a bummer that those evil people back then did this right. And you don’t realize that some of the residue of a lot of the residue of the dynamics of how that worked then are working now.

Aurora: Exactly.

Jeff: that’s where that’s where once you have these realizations, you now become responsible. You become when you’re aware, you become responsible. And so that probably is one of the most interesting current dynamics is are my conversations with other people of faith, because it is not well understood. It is very defensive when you you point these things out and then immediately gets into the political dismissal. Yes. Oh, you must be a Marxist. You must be you know, it’s the social media, you know, implications of our culture now. But no, I’m a Bible believing Jesus, loving evangelical. That’s like if you had to just get to the heart of my theology, I believe in Jesus and his resurrection, his sacrificial purpose, the inspiration of all these things that if you looked at that most people would throw me into a very conservative Republican, whatever sort of category. But I’m not. And it’s because I’ve I think I’ve understood a little deeper the the politics and the theology of power and privilege and how that has seeped into all aspects of our faith, our culture, our economics.

Aurora: And so unpack that a little bit for us, because I think the intersection of economic economic power and religion is something that is very tenuous for most people, and it is. So share with us what you have unpacked in this process of transformation and introspection.

Jeff: There’s a quote in my book, and I’m the worst person to quote anything, including my own writings. I basically. I realized that when economics and theology are up against each other. Economics wins, people are will figure out a way to twist theology, to pursue the economic goal instead of the other way around. You know, if we really lived by the themes, the words, the example of Jesus and frankly, many other teachers, our economics would be very different if we if we adapted the economics to what we say we believe. I mean, how different would this world be? But it works the opposite way. It actually the theology, the the cultural elements of of a faith that get twisted to support the economics. And, you know, you could argue that that’s, you know, sort of Maslow’s hierarchy, you know, you know, when people are threatened or they’re enticed by greed, a lot of the other elements of our fulfillment get subjugated to that fundamental purpose. So that’s that’s a big part of it.

Kelly: Whoo!

Kelly: So once you started to understand your racial identity and then you’re kind of looking around like, oh, I was culturally appropriating or I’m that gentrifier or I’m, you know, this church is really white or, you know, you start seeing all these realizations in your sphere of influence, spheres of influence. What helps keep you searching and drawing through to get to the not to the other side of this, but to to keep pushing you for what what’s what keeps propelling you?

Jeff: I think they’re kind of two things that help me. One is what, maybe three. One is when you taste. Something new. That that reprograms your brain a little bit, and I’m a big believer that for people to overcome any habit, any addiction, any, you know, maybe negative pattern in your life, you can’t just tell people to stop it. You know, you got to tell you’ve got to show someone a more powerful and joyful way. You know, you have to be able to trade something negative for something really much more positive. And so a lot of what keeps me going is those little flickers of joy and epiphany and peace and connectivity with new friends that would be completely shut off to me if I had not been going down this road. And so. I think that’s a motivator, you have to have a motivation, you have to have your WHY. And so that’s a big part of it. Another part of it is – there’s a chapter in the book about how our brains work. And it’s it was it was very discouraging to me how quickly some of the progress that I had made, being very comfortable and even eager to be around people of many different cultures, skin tones, whatever. When I lived in Philadelphia, how quickly I lost that. When I moved back to West Virginia for a few years and I lived in a white neighborhood and I lived in a much larger, more homogenous society, again, my brain just started to get those old patterns back. And so when I came down here to Nashville and we were looking for a place to live. I almost it was almost too late, but I caught myself in autopilot and I and I write about this where I need to find a safe neighborhood for my daughters to live in. And so all those little tropes, all those little subconscious things started working towards guiding me down a path about where I was going to live.

Aurora: The oxygen.

Jeff: Yeah. Yeah. And it was almost at the last minute that I finally caught it and I was self aware about it. I was really ticked off at myself for allowing that to happen, but. I needed to explore why that was what one caused me as someone who has not building myself up in any way, but compared to the average white person, much more educated on these topics than many. But yet I still fell for it. I still fell for it. Almost fell for it. And so I needed to write that chapter about how the brain works so that I can understand why does that keep happening to me. So that’s a big part of it, is realizing that we now have a responsibility. Again, once you become aware, you become responsible. I know that if I don’t purposefully infuse my life with diversity, with influences that are maybe countercultural to what the broader society is sort of leading me down. If I don’t purposely change that, I will go back to how I thought before. And the final third piece, which is really important as I now have a Brown family, I have I am married to a woman of Indian descent who grew up in Spain. I have two stepdaughters who are Indian, and there’s not a day goes by now that it’s not front and center for me about how they are doing, what is their experience, what is their life like. And they’re. Burden as growing up into a teenager hood and experiencing some of the things that they’re now experiencing. There’s no way I can’t feel that as well. And so that’s that’s a very much a built in motivator as well.

Kelly: So, yeah. Yeah. The science part is so interesting to me because that’s a that’s a self. That’s an introspection I didn’t do. And that was really helpful to read. What other types of introspection besides your how your brain works, you know, did you come across was there anything having to do with. For me it was therapy and trauma and and things that I was reacting on and and feelings I wasn’t feeling. And sort of just in unpacking the programing of whiteness, you know.

Jeff: I’ve already spoken a lot about some of the spiritual elements of itSo I think that’s a very big deal. But the other big piece of it for me, and this is where it gets maybe a little controversial, and I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. But, you know, there is a real sensitivity to white people going to friends of color and saying, teach me, you know, help me understand this. And and so I’m very aware of that at the same time. I think there’s a lot whether that’s a positive experience for both parties has a lot to do with how you approach it, obviously. And so I have to honestly say it’s not just Crystal, but a dozen or more friends of color that we’re willing to talk to me as I ask them questions about their life and their experience and. What whiteness was doing to them. That was one of the most emotional parts of the whole journey because. And I interviewed several friends. And, yes, it was under the you know, I knew them well enough to be able to ask them, but I literally just asked them these questions. What does it feel like when this or what did that trigger in you or what is your experience? And I think I cried in every one of them and every one of those conversations, which, again, I know is a little bit like, oh, white tears. I think. If you don’t mourn injustice and the feelings of what your friends have gone through, I don’t know if you have any emotion. I really don’t like to hear the things that my friends went through that I didn’t even have. The wherewithal to ask them in the past that really floored me that because one of the very common responses was Jeff, no white person has ever asked me. How that has affected me. I just feel emotional now talking about it, it’s it’s crazy, it’s just, you know, so, yeah, if you are willing to open yourself up to the connection of another human being and you hear that it will change it. It can’t it can’t help but change it. And you have to like I said, the brain can very easily go back to old patterns. So I want to constantly stay in an open stance of listening throughout the rest of my life. And that will help.

Aurora: Well, that’s actually the word I wrote down when you were you were sharing this story, Jeff. I actually think that you not only leaned in with your heart, you opted in with your heart, but you listened. You know, you asked the question of your friends, but you actually listened to their response. And I think, you know, if I would offer something to white people is that they’ll ask the question and they’re asking the question to find a way to defend the position or. Yeah, or find the exception. And so it’s like, no, just just listen. Just hear my story and hear what I felt, because I don’t have to defend how that landed on me. I don’t have to defend how it felt. And I think that that’s one thing that I hear and what you you are sharing that I think is so important for white people to hear is that if you’re going to ask a person of color to share their story. Open your heart and listen, no. That’s it, there’s you don’t have to say anything, just listen. So thank you for that, because I think that is extremely, extremely powerful. And the other thing that I’m hearing from what you’re sharing is that there is this thread of intimacy. There is this thread of trust and you putting yourself in environments or situations where you were able to foster connection and relationship relationships with people that didn’t look like you. And I think that’s also extremely hard for white people. You know, we walk into our corporate environments, you know, there’s still 90 percent white. Yeah. And oh, by the way, if we do have a significant portion of our organizations that have people of color they’re in and not in a part of an organization that most of the people, white people don’t sit in. Right in the back office, part of the organization operations, but not in the front end customer facing in a pervasive amount of numbers, and so white people spend their entire lives swimming just in the oxygen of whiteness.

Jeff: Mm hmm. Mm hmm. Yes, the thing that was, again, very. Disruptive for me was, again, how that is true in so many parts of life. Yes, it’s it’s the corporate world that I’ve been in, but it was also my neighborhood. It was also my church. It was also my school. Think about that. I mean, everywhere we go, the culture has divided us into these pockets. Yes. And that’s what makes it so fascinating when you are at a sporting event, you know, been to many Eagles games. Right. The level of cross racial joy and high fives and hugs in the stands that you would never, ever see anywhere else in any of the other pockets of our lives. I just think that’s really fascinating to sort of people watching those environments. And and you start asking yourself, this is all very possible. The other thing that gives me hope is I think this goes a little bit more back to how our brains get formed. But, you know, I was a little disheartened at first when I saw the research that little toddlers can have racial preferences. If you sort of throw a bunch of toddlers of different races in a room at a certain age, they really do start gravitating towards each other like the black kids go here, the white kids go here. And and I’m like, oh, gosh, is this just embedded in our DNA? Is this what, you know, the tribalism that we’ve just inherited through through evolution or whatever mechanism? And then I found the rest of the research and the rest of the research shows that, no, when a baby is brought up with images and relationships and connections of diversity in their life, they’re that that sort of self-selecting into different groups doesn’t exist. So in other words, that baby’s brain has has been impressed that this brown person, this black person, this white person, whatever categories, these are all safe people. These are all people that love me. These are all people that provide for me. It’s rare. And that’s why segregation and some of this other stuff is so dangerous, because we keep bringing up generations of kids who are only brought up in their. Homogenous kouakou, and that kind of perpetuates the stuff.

Kelly: Well said.

Aurora: So, Jeff, you know, you had Crystal, who you had been building a relationship with for, I think a couple of years, that allowed you to receive a text that to to receive it and really receive it. I love how you said that. Just let it sort of bounce off of you. We’re at a moment in our in our time, in our history, I think we’ve had many, many moments, right. You know, brown and black people are like, yeah, we’ve been talking about this for a long time. How how would you offer what is your offering to white people as you see the journey that you’ve you’ve traversed and self introspection and self transformation, racial literacy, racial identity, owning and knowing your whiteness and being able to see it and call it out. How do other white people get there?

Jeff: Really quick story, I was in Philadelphia, I was pretty young back then, I went to a church back then called Circle of Hope, and this church invited a local poet. I guess I hang around with poets and activists a lot because he was another one. But he came into this church a very wide eyed, eager, ready to do good young white people like that. That’s what the congregation sort of looked like. Right. And so this guy comes in. He’s African-American. Long hair, I just sort of describe him because of the difference and and and just sort of imagery there, but he had dreadlocks, he came in, he just sort of stood up there and he was going to speak about racial justice. And so we’re all sitting there as these eager kids like, great, we’re on board with this. Tell us exactly what we need to know. And the lot of these people were moving into West Philly, North Philly, trying to purposely place themselves and in areas where they felt they certainly they’re going to experience diversity, but they’re also there to help, there to help serve there, all that stuff. And this guy stands up and he says. What are you guys doing moving into our neighborhoods and you could just see everyone’s faces like, wait a minute, I’m on your side. You don’t get it. We’re we’re the good guys. We’re here to be with you. And it was just so I’ll never forget that that experience, because what he ended up in and he wasn’t trying to be rude about it or anything, he was just calling out the fact that, look, if you want to help. Go back, talk to your white family friends, go back, challenge white supremacy, challenge white privilege, challenge these systems. That’s what will help us. And so to answer your questions are for the long sort of answer. But the challenge for me, the challenge for anyone else who reads this book or, you know, wants to do good is to get on the journey. You have to get on your own journey. You have to educate yourself. There are so many things that if you could read some of these books or educate yourself, you don’t have to go to a person of color to fill in the blanks and and trigger them to have to experience all the stuff all over again. But you can now come to them and say, I just want to know about you. How are you? How can I be your friend? How can I support you? How can I be an ally or any word that you might use there, but. You know, that’s that’s what I feel like we need to do. White people have to begin educating other white people in order for this to work.

Kelly: So agreed. I have a fill in the blank for you. Giving up whiteness. Gaining blank.

Jeff: Giving up whiteness, gaining really rich human connection. I feel so much more connected to everybody. And. I’m not going to put a Pollyanna spin on this to say all my black friends are my favorite friends. But what I’m trying to say is that the richness and of the experience of being friends with everyone, there’s not a barrier in terms of how I could say I’m going to be a close friend to this person that is powerful. That is that’s that’s the motivation. Right. That’s the joy that opens up to you when you’re willing to let these things, you know, the whiteness identity when it comes down to the identity of connecting to other humans, to having self-esteem based on other identity elements that are much healthier and positive that you can share with other people. That’s that’s where that’s that’s the fill in the blank. That’s the motivator.

Aurora: So that’s actually where I wanted to go with the with the fill in the blank. Jeff is like, how has it changed your life? Right. Because I think for white people who here, you know, it gives you human connection. I don’t know that they know what the other what the other benefit what the benefit of that is. So so share with us. How has it changed you? What is the benefit that it has given you? What is the benefit it is given your work, what is the benefit? It’s given your family.

Jeff: Well. I don’t know if we have time to go through every all, but I will say that the benefit in each category of life is very similar. Could I be? I don’t want to get emotional again when I think about my daughters, but how could I be? A healthy father figure for my two stepdaughters, yeah, if if I wasn’t. At least on this journey, I couldn’t I couldn’t help them. I couldn’t even really I wish we had time to go into some of the conversations that we have as sort of father and daughter. Now, it’s amazing. I couldn’t be an advocate for friends and colleagues at work. Yeah. That I’ve tried to be. You know, we’re going through at my current employer the aftermath of Black Lives Matter movement this summer. And just everything all these institutions almost seem like, wow, maybe we actually have to do something this time. And and it’s happening anecdotally. It’s happening and. Quick, quick, quick example, three years ago, I went to war, I probably can’t tell the full story. Let me just say this. In the past, I’ve gone to H.R. and said we are really kind of missing out on the benefits of a more diverse workforce, innovation, performance, ideas. It’s all there in the research in terms of diverse organizations. And the reaction was. Very defensive, right, like, oh, so you’re saying we’re racist company or you’re saying that we don’t want to hire black people? No, I didn’t say that. I said we need these benefits. So, you know, fast forward to now. Yes. Because I did that, H.R. proactively called me and also I was very blessed to be included and the employees of Color Informal, my working group that sort of like emerged in response to this, like, you know, I was blown away that they would feel safe or to invite me into that. And none of that would have happened if I hadn’t have been on this journey the way that I have been. And so, you know, it’s some people say, well, it’s kind of like eating vegetables and just being a healthier person. It’s not like that. It really is like. Having a lot of desert because it tastes good, it’s good. It’s really joyful. It’s not I mean, it’s hard. It is hard. So maybe you have to go through a little bit of vegetables to get to the desert, but it’s hard. But when you finally, you know, you get to that place where you’re not so self-conscious that you prevent yourself from being a friend to someone else, to being an ally for someone else to, you know, asking somebody how they’re doing. I mean, if you limit yourself from that, you’re limiting yourself from life. Yes. I mean, that’s that’s what life is. So.

Aurora: Beautiful, beautiful.

Kelly: So what’s your opt in for our listeners today, Jeff.

Aurora: What can I can I, can I make it more specific. Because Jeff, I have to tell you, I continue to be fascinated by white men and I don’t I don’t really know too many, to be very honest. I don’t I don’t actually think I could count them. I they couldn’t make up beforehand that I can say that I believe are earnestly and genuinely and courageously and curiously on a path of self transformation to unpack whiteness, to unpack white supremacy, to unpack white privilege within themselves. And so my question to you. Is what is your specific opt in for white men and then I’d love, you know, and what’s your what’s your opted for white people in general?

Jeff: Men still are very programed to feel like they’re supposed to be the protectors, the strong ones, and particularly in places like the church, they feel they are the protectors of theology, protectors of truth, protectors of what’s right and. That can lead many white men down the path of certain political positions, certain theological positions that are very. Inflexible and very harmful for people that aren’t white males. And so it’s kind of I guess my opt in for white males would be what I would say for them to be. In almost any other category, which is what’s your definition of strength, what’s your what’s your definition of. A male identity, yes. And is that definition? First of all, is it fulfilling to you, because I tell you, a lot of men will admit it, but when you do get them to admit it, a lot of men aren’t that happy. Honestly, it’s like, you know, which is why I think you see some of the rage going on out there. It’s there’s not a lot of happy, fulfilled men. And it’s because they’re kind of trapped in that identity. And so I would I would ask the ask white males to just really opt into understanding your own identity in the definition of a strong male. And how does that definition. Affect women around you, people of color around you, children around you, all of those things. So there is a there’s an element of that that’s just that’s so gender oriented in our culture that that I would have to call out and then broadly for for for just white people. It’s very similar in terms of that identity. But I would say that opt in is a little more on that positive side, which is get on a journey where you feel connected to a lot more people. I mean, we’ve all seen the loneliness research, right? Yes, everybody is struggling. Everyone is lonely with all the social media. You know, people are just incredibly lonely. And I would say that that does not have to be that way. And the ability to feel an equal connection to any other human to to be able to say this particular problem in our society is not their problem. It’s our problem. And to be not carved out in this insecure barrier of like, well, I’m not even welcome to participate in that. Or if I do feel motivated to help, it’s it’s like I’m going to I’m going to help these poor people like, no, no, no. Like I always say, you know, when when I help someone, I benefit 10 times more than that other person.

Aurora: Absolutely beautiful. Jeff, before we end, is there a question that we that you would have liked for us to ask you, particularly as it relates to any key point in your book? That we may not have today. That you think is critical.

Jeff: Wow, you guys have covered a lot of a lot of ground here. I will say maybe maybe this. And I also think, you know, coming from Appalachia, there’s and this actually is a believe it or not, this is an area where Crystal and I are connected right away. She’s a huge advocate. She’s a part of this poets group called the Appalachian Poets and for African-American Appalachia. And, you know, it’s really interesting because, you know, barely three percent of West Virginia is African-American. So it’s a very small community. But the legacy and the history of coal mining and African-American coal miners, you know, in a way, all these it’s just fascinating. And she is the biggest advocate of West Virginia that you could ever find. And so the reason I bring that up is. As the Appalachian people, this goes to a little bit of hillbilly elegy kind of ramifications, but. That is an example of identity and culture in a subset of white culture that people don’t realize. That we are the other Appalachians are the other also in white culture and growing up like that. I think also created a sensitivity of of the underdog injustice, generational patterns of oppression, which have absolutely happened in Appalachia. There are many, many people that have taken that legacy, and they again, they’re clinging that it’s it’s made them very defensive and insecure and angry and willing to vote for certain people that really don’t have their interests in mind. But they feel like, well, finally someone is going to speak up for me. Or it can teach you. That I know what that feels like, I know what the fuck’s in the book, you know, the sort of the pressure of systematic things can can put on people. And so that’s just another element of my story in the book that sometimes people miss because it is a little stereotypical to think of what an Appalachian experience is like.

Aurora: Well, we certainly hope that all of our listeners reach out and pick up your book, A Christmas The Holidays Are Coming Giving Up Whiteness by Jeff James One Man’s Journey. I personally, Jeff, can’t thank you.

Jeff: And ahead, we’re all going to break down for having this conversation today.

Aurora: Thank you. Because there’s there’s moments where there’s so much rage for me and it’s and it’s the praying and it’s the finding of the hope. And, you know, for me, it presents itself a lot as anger towards, you know, white male gender. And because there’s been so much harm at the at the end of that spear. And so I. I thank you for. Stepping into the journey, you know, creating an incredible book that reveals what? Your steps were, and I so, so hope. That white people pick up this book and find a moment of. Of hope, of light, courage and curiosity to take on their first step into the journey as well.

Jeff: Yeah, I can’t tell you how much that means to me that, you know, it has affected you guys and anyone who’s read it. I don’t take credit for it and I honestly don’t. I feel like it was a God thing and I don’t know why it happened. But it happens. And here it is. And I’m so grateful. I just I’m so full of sort of joy that that is affecting people in the way that I had hoped it would. So thank you. Thanks for even sharing them.

Kelly: What did you think?

Aurora: I mean I think we need to GET this book out there! I know a lot of people who need to read this book.

Kelly: Thank you all for listening. Find us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram @the opt in.

Aurora: Music for this episode is by Jordan McCree. And the Opt-In is produced by Rachel Ishikawa.

Kelly: See you next week.

Aurora: Bye